The Christian Hauran

When we speak about the Christian heritage in Jordan, we think before all to the famous sites located on the highlands overlooking the Jordan Valley, along an axis followed by the classic pilgrimage itineraries, easy to link with the Dead Sea and the Baptism site. We often ignore that Jordan teems with Christian faith testimonies widespread over the whole country till the edge of the desert. A good example is Umm Al Jimal a provincial town build in basalt and flourishing during the Byzantine period at the limits of the Eastern Black Desert, which alone accounts not less than fifteen churches.

This heritage is especially impressive since the town remained inhabited for about 1100 years: the earthquake of 749 AD, followed by a pandemic and geopolitical changes fatally disrupted its prosperity and slowly depopulated the settlement. It is only at the 20th century that a Druze community occupied the ruins and refurbished the houses in order to make them livable. They abandoned the site in 1932, letting the room free for a Bedouin tribe that used to periodically come on the area. The Bedouin settle in the houses for some decades before building the adjacent modern village. This mean that, roughly speaking, we are in front of a town as it was at the Byzantine time. The transition to the Early Islamic period did not fundamentally modify the structure of the town, nor even the life of its inhabitants. The 20th century settlements only brought minor changes to the buildings. We could even say that in a certain point of view, they contributed to the buildings preservation.

|  |

Umm Al Jimal is located at the junction of two wadies, in a steppe zone called the Hauran extending between the basalt slops descending from the volcano Jabal Al Arab or Jabal Druze and the more fertile western areas. Even if human activity can be traced back till to the Neolithic, the first settlement takes shape relatively late, at the 1st century AD, when the whole area between Petra and Bosra is under Nabataean influence. During the different periods of occupation stringing from the 1st to the 9th centuries AD ( Nabataean, Roman, Byzantine and Early Islamic periods), Umm Al Jimal is a satellite agglomeration of Bosra, as well as the other settlements of the nowadays Jordanian Hauran. All those cities are part of a specific Hauran culture, especially recognizable in architecture. Umm Al Jimal never received the coating of the Roman urbanism, so noticeable in the Decapolis cities: no cardo, no theater, no monumental fountain... the agglomeration is a typically and deeply Arab, with houses grouped in clusters and a rural economy.

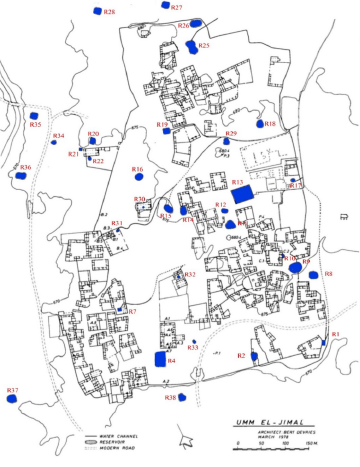

Umm Al Jimal map with water points

S. Bradley, J. Eisenhart, N. Szott, R. V. Meulen art., ref. below

S. Bradley, J. Eisenhart, N. Szott, R. V. Meulen art., ref. below

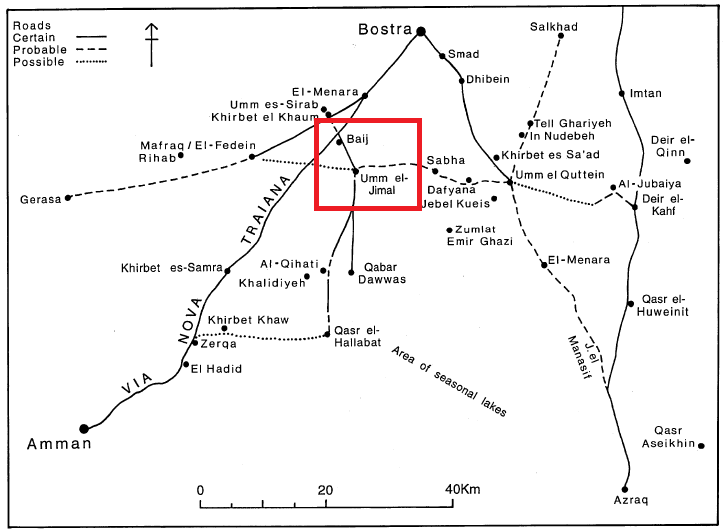

Umm Al Jimal holds a particular location, approximately at the crossroad between the Via Nova Trajana, this important communication axis linking Aqaba to Damascus via Bosra (passing 6 km West at Ba'ji, where Romans build a fort) and a secondary axis toward East along which a series of settlements string out, among them Sabha, Um Al Quattain and Deir El Karf, all of them containing antique sites.

David Kennedy art., ref. below |

The peaceful life of the village seems to have been brutally suspended once during its history, probably during or subsequently to the civil rebellion against Rome leaded by the Queen Zenobia of Palmira at the middle of the 3rd century AD. Further to those events, the Roman authorities strengthened their military presence and Umm Al Jimal, integrated in the fortification system of the Eastern Roman Empire frontier, had to host a garrison, military infrastructures and an defensive wall.

Praetorium in 1913 | The "Barraks", Roman cavalry fort |

Butler art., ref. below |  |

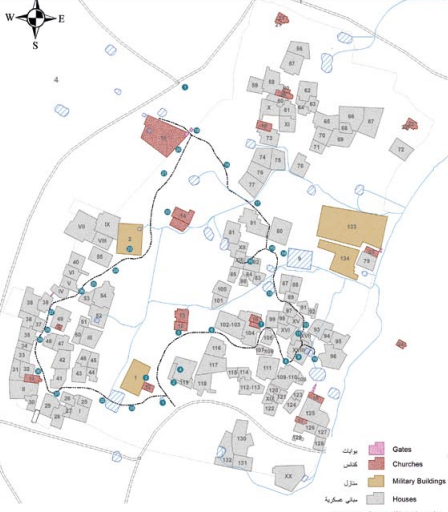

This military occupation fell in disuse at the 5th century, with the advent of the Byzantine Empire which insured the city with a peaceful prosperity, between farming and trading. The military infrastructures were converted to civilian use, sometimes flanked with the symbol of the cross, and remodeled. One of them became a monastery. The new period, that brought the dislocation of a presence probably perceived as an occupation together with a new religious philosophy totally dissociated from politic and addressing to the heart of people, gave a real impulse and a new inspiration to the society. During the 6th century, the population may have reached 8000 inhabitants. By the end of the 6th century, Umm Al Jimal included fifteen churches and chapels inside the urban structure of about 150 houses. About the half of them were built in the immediate neighborhood of domestic structures, even sometime directly connected to a private domain. This imbrication of the religious space with the private space indicates a intimate, personal and intensive practice of the new faith. People decorated the lintel of their private entrance with the Byzantine cross. Private families sponsor the erection of a church and let a dedicative inscription mentioning their name. The density of the religious building comparing with the population size is not only explained through the vigor of the practice but also the custom of the votive offering inherited from antic practices: in the wealthy society of Umm Al Jimal, it is not a pillar, a statue or an animal but a whole construction that is offered to God. That is to say that after the abraded antic religious syncretism and the political constriction imposed by Rome, the inhabitants of Umm Al Jimal experienced a real spiritual revolution and a new breath.

Umm Al Jimal map with the churches and chapels in red | Church | cross on the arch of the cathedral |

ACOR newsletter, ref. below |  |  |

Most of churches were built at the turn to the 6th century. Some of them underwent a remodeling at the end of the 6th or at the 7th century. Many buildings contain mosaic floors with floral, animal and geometric patterns. It is interesting to notice that the Umm Al Jimal mosaicists who worked in Umm Al Jimal never reproduced the figurative Greco-Roman scenes and personifications that we can see in the more western areas as Madaba and Um Al Rassas. The mosaic style is simple and neat.

The emergency of Islam did not cause any turmoil. The transition to the Early Islamic period is progressive and smooth. At least two churches, maybe three, were converted into mosques, while others kept their original services and even underwent renovations at the 8th century. This continuity suggests that both religious practices lived side by side and that the society kept its harmony.

Other interesting features of Umm Al Jimal

What appears striking at the first sight of the visitor is that the whole city is built in basalt. This characteristic gives to the city a dramatic atmosphere that the photographers will enjoy. The other Hauran settlements use the same material but Umm Al Jimal is an extended site (more than a half kilometer square) with buildings conserving time to time their second floor and windows. |  | ||

| Umm Al Jimal architecture is typical of the Hauran region, using for the roofing large basalt slabs leaned on corbels that are themselves smaller slabs integrated in the walls. This technique is extremely old in the context of the buildings made of basalt, as it seems that the roof of the square building at the top of Jawa site, dating back to the Bronze Age, uses the same method. Even, Neolithic huts in the Eastern Badia already present slab roofing leaning on a kind of corbels. We can see the same type of construction in the Azraq Castle. This technique, called corbelling, induces the rooms to be narrow, as the ceiling must be closed by slabs that should not be too elongated to avoid breaking. However, it makes strong structures that allow the erection of a second floor. | ||

Many houses present an ulterior ceiling support technique added to the structures at the late Ottoman period when the Druze settled on the site: longitudinal arches were built inside the rooms in order to consolidate the whole. It is easy to recognize those adjunctions as the angles with the original wall do not present any anchorage. |  | ||

| Another particularity very manifest in Umm Al Jimal is the external stairways built of slabs also integrated inside the walls. | ||

Many houses include animal mangers in the lower floor. Those structures have mostly been added at the Early Islamic period, indicating the importance of animal husbandry at this period. |  | ||

| An excellent water system including several cisterns, aqueduct and canalizations was used till very recently by the Bedouins. The largest cistern dates to the Roman period, but others date back to the Nabataean period. | ||

Umm Al Jimal is home of hundreds of inscriptions in Nabataean, Arabic, Safaitic, Greek and Latin scripts, a precious source to decode the social and religious behaviors, the relation to power as well as the profile of the inhabitants. It is for example through the names founds on the tombstones and the dedications that we know that the population owned to an Arab background. Also from the inscriptions we can see that the religion in use before Christianity was a like a syncretism mixing Nabataean divinities from South and North of the Nabataean influence zone with names borrowed to the Greek pantheon. Some Nabataean inscriptions are particularly relevant as they demonstrate a script evolution toward the Arabic cursive writing. Another feature is the reuse of the engraved stones in the domestic sphere in a later period. Therefore, we can find an inscription or a part of it included in a wall or a door frame... |  | ||

Many tombs have been discovered, a few on the site but mostly in its vicinity, as cemeteries extended outside of the city walls, so that archaeologists could survey human remains, funeral material and burial practices. Tombs of different typologies have been excavated: cist graves, pit graves as well as monumental chamber tombs. Even if several tombs were spared of robbery, the situation that archaeologists found is complex due to a phenomenon of re-use of the graves over the time and the periods. Isolated monumental chamber tombs scattered more far from the city suggest that some wealthy families buried their member on their agricultural lands. |

Other Byzantine cities of the Jordanian Hauran

Far of being an unique urban center in the South Hauran, Umm Al Jimal was part of a group of plus or less developed settlements that gravitated around Bosra. Most of villages of the Jordanian Hauran conserve today remains similar to Um Al Jimal but at a smaller scale:

Samah Samah |  Umm Es-Surab |  Umm Al Quttain Umm Al Quttain |

Sabha Sabha |  Deir Al Kahf Deir Al Kahf |

References:

www.ummeljimal.org and particularly the articles of the page www.ummeljimal.org/en/library.html

D. Kenney: www.academia.edu/11662334/Roman_Roads_and_Routes_in_North-east_Jordan

Sarah Bradley, Jason Eisenhart, Noah Szott, Ross Vander Meulen : http://engr.calvinblogs.org/17-18/srdesign04/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Senior-Design-Presentation-2.pdf

Butler, H.C.: www.ummeljimal.org/doc/Butler%201913a%20Ancient%20Architecture.pdf

ACOR: www.acorjordan.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ACOR-Newsletter-Vol.-28.1.pdf